Introduction

Lecturing on the introduction of public libraries across Britain in the mid‑nineteenth century, John Ruskin reflected on the many letters he received from parents concerning the education of their children. In this “mass of letters,” he noted that he was consistently struck by the precedence given to the idea of a future “position in life” above all other educational considerations. Parents, he observed, rarely sought an education that was good in itself, but rather one “which shall keep a good coat on my son’s back; which shall enable him to ring with confidence the visitors’ bell at double‑belled doors; which shall result ultimately in the establishment of a double‑belled door to his own house” (Ruskin, 1985, p. 255).

Since Victorian times, education has increasingly been justified in terms of economic success, employability, and measurable outcomes. Yet the word education derives from two Latin roots: educare, meaning “to bring up,” and educere, meaning “to draw out.” A good education, therefore, may be understood as one that both nurtures the individual and draws out what lies within them, while also enabling meaningful participation in the wider world.

This question takes on renewed urgency in the context of the early twenty‑first century, particularly in light of rapid developments in artificial intelligence and data‑driven technologies. These developments are reshaping not only how education is delivered, but also how it is justified, measured, and governed. In this essay, I focus on the 2 Hour Learning (2HL) model and its network of Alpha Schools, which use artificial intelligence to deliver a highly structured, personalised, and metric‑driven form of education. I examine both the pedagogical model they present and the ideology that underpins their use of AI.

My analysis is informed by my own experiences of education, particularly my time in secondary school and my later work as a tutor at Ruskin Mill College, which offers a place‑based, therapeutic curriculum for students with special educational needs.

I argue that while models such as 2HL may appear to offer an efficient solution to perceived crises in contemporary schooling, they risk narrowing education to qualification and performance, leaving little space for the free and holistic development of the human individual. Drawing on Gert Biesta’s distinction between qualification, socialisation, and subjectification, as well as Rudolf Steiner’s conception of education as belonging to the cultural sphere, I explore whether AI‑driven models can genuinely support the formation of responsible, ethical, and free-thinking students.

2 Hour Learning

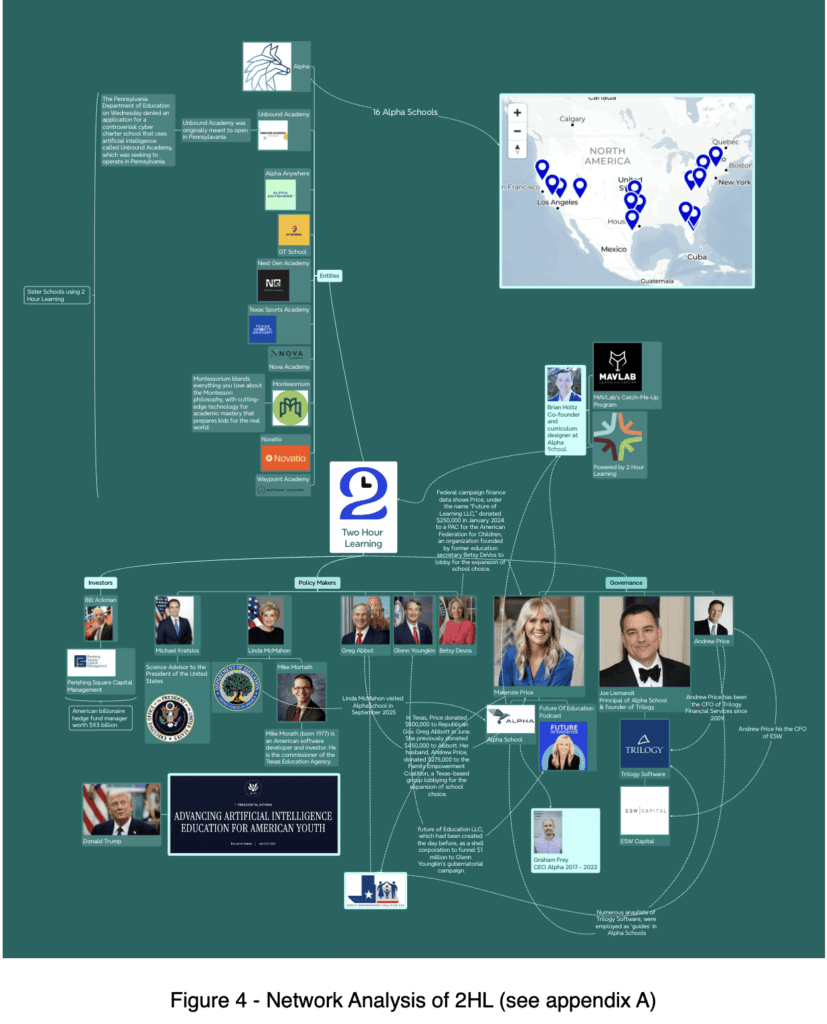

Over the last few years, there have been major developments in artificial intelligence, paving the way for what some claim is a revolutionary approach to education. Alpha Schools are a network of 18 schools across the United States that use AI to deliver two hours of personalised academic learning each day, freeing up the remaining four hours for developing life skills and personal interests (2HL White Paper, 2024). Students at Alpha Schools consistently achieve results within the top 1% of U.S. students academically, although most come from privileged backgrounds, which may be a filtering factor in these outcomes. The 2HL programme underpins all 18 AlphaSchools, more than ten affiliated schools (such as Texas Sports Academy and Montessorium, which blends the Montessori approach with AI-led academics), and Alpha Anywhere, which allows students to access 2HL from home (Alpha Anywhere, 2025).

Since beginning to write this assignment, the number of schools has continued to increase, suggesting growing momentum and global ambitions. I have also noticed how the slick marketing, and tightly controlled image is beginning to show signs of cracking (Feathers, 2025; O’Hagan, 2025), and how recent revealing accounts from students, staff, and parents show two sides to the story, and reminds us how the battle for the future of education is unfolding before us in real time.

Joe Liemandt, founder of Trilogy Software (which owns 2HL) and Principal of Alpha Schools since 2022, said on a podcast in August 2025 that “[generative AI] is finally the technology that is going to allow education to scale and we can take all this awesomeness where kids can learn two, five, ten times faster and get it out to a billion kids. That’s when I became principal because I was like, okay, Mackenzie, we could totally make this… a super scalable thing.” (Invest Like The Best, 2025)

MacKenzie Price, founder of 2HL and Alpha School, is the most prominent figure propounding a model of AI-driven, personalised education. Over the past year, she has become increasingly visible online, amassing over one million followers on Instagram and appearing on an array of high-profile podcasts, and television interviews. In September 2025, Alpha School in Austin, Texas, hosted the U.S. Education Secretary, Linda McMahon, who, following the visit, stated: “Harnessing AI thoughtfully will be critical to expanding opportunity and preparing students for tomorrow’s workforce.” (Alpha School, 2025d ; U.S. Department of Education, 2025). While many alternative educational models remain on the fringes, it is conceivable that the Alpha Schools model will continue to expand rapidly, due to its positioning and influence.

You will not find any academic teachers in an AlphaSchool; instead, you will find guides who “motivate and support students as they become self-driven learners” (2HL White Paper, 2024, p. 3). Similarly, at Ruskin Mill College you find tutors who work with students toward developing “self-generated conscious action”, and motivation and support is key to help students engage and assess the diverse, and research backed therapeutic curriculum. At AlphaSchool, these guides motivate students to complete their two hours of AI-facilitated learning, then spend the remaining four hours of the school day helping them pursue their interests and providing workshops. One of the core tenets of Alpha Schools, is that “your kid has to love school more than vacation” (Alpha School, 2025b), with high school students reportedly asking to keep the school open during the summer.

The split between two hours of AI-personalised tutoring followed by four hours of free time makes this model of education highly appealing within the current educational paradigm, as it appears to answer the needs of students and parents, while radically changing—or discarding—the traditional role of the teacher. Economically, although AlphaSchools currently charge around $40,000 – $75,000 (in San Francisco) per student per year (Alpha School, 2025a), the fundamental 2HL technology is scalable at relatively low cost.

In most Alpha Schools there is a ratio of one guide for every five students, with guides tasked with motivating students. Interestingly, in the new ‘proof of concept’ Alpha School, in Brownsville, Texas, next to SpaceX, where tuition is $10,000 the guide-to-student ratio increases to 1:20 (Wallach, 2025). This indicates that parents unable to afford an elite education will have to settle for a much higher student-to-guide ratio, without the same level of human support as found in the pilot Alpha Schools, and as Alpha School scales, as a privately owned company, it is likely to see a reduction in paid ‘guides’ especially when the tuition fees per student are lower.

The ‘guides’ are often recruited from senior positions in mainstream schools, Price says they hire people who may have no teaching qualifications but have mastery in business, or other domains. Their task is to motivate students to be self-driven learners, and they are paid between $100,000 and $150,000 (Alpha School, 2025c). Wired magazine (Feathers, 2025) reported that, of the 31 guides employed by Alpha School during the 2023–24 academic year, 26 were shown through their LinkedIn profiles to have previously worked as analysts for Trilogy Software or other technology organisations owned by Joe Liemandt. This concentration of backgrounds raises concerns about the formation of an educational echo chamber, in which professional educators are displaced by individuals whose training emphasises measurement, efficiency, and data-driven optimisation, potentially at the expense of relational, pedagogical, and human-centred educational practice. As Steiner wrote: “The growing human being should mature with the aid of educators and teachers independent of the state and the economic system, educators who can allow individual faculties to develop freely because their own have been given free rein.” (Steiner, 1919)

Teacher unions have expressed strong concerns about this trajectory. Arthur Steinberg, of the American Federation of Teachers, responded to Alpha’s cyber-charter bid in early 2025 by stating that, just as districts would not accept students using AI to write their essays, they “will not accept districts using AI to supplant the critical role of teachers” (Steinberg, as cited in Alexander, 2025). This points to a central tension in the 2HL model: whether education is to remain grounded in human relationships and pedagogical judgement, or whether it will increasingly be reorganised around platforms, metrics, and scalable AI solutions.

Looking At The Policy And Its Network

The 2HL white paper is presented in a manner strikingly similar to an education policy document; even the term white paper originates in government. It defines a crisis in contemporary schooling in emotive and compelling terms, then proposes a comprehensive solution and outlines detailed mechanisms for tracking student progress through metrics and data dashboards (2HL White Paper, 2024, pp. 21-23)

I believe that a vacuum is opening up in education due to growing cost of living and the rapid advent of artificial intelligence. 2HL and AlphaSchools are well positioned, and well connected, to influence education policy in the United States and potentially beyond. In this section I conduct a discourse analysis of their 33-page white paper, alongside a policy network analysis (Ball, 2016), to understand why they are gaining such momentum and influence. Although I fundamentally disagree with the ideology underpinning these schools, I have to acknowledge that, within the current paradigm at this stage of the twenty-first century, their model is likely to be perceived as a “good education” by many parents and policymakers.

2HL cite Benjamin Bloom’s work on “the two sigma problem” (1984), which showed that students tutored one-to-one performed on average 98% better than students in conventional classrooms. Bloom concludes his paper by noting that “the search is far from complete. We look for additional solutions to the 2 sigma problem to be reported in the next few years” (Bloom, 1984, p. 15). Forty years later, 2HL claim that their model is the answer, as it gives every student in the classroom a one-to-one tutoring experience—not with a human being, but with artificial intelligence ( White Paper, 2024, p. 20). A traditional classroom of thirty students poses many challenges: the teacher must pitch the lesson to reach the greatest number of learners, meaning some students fall behind without fully understanding the material, while more advanced students may have to sit through content delivered well below their potential. Kestin, Miller, Klales, Milbourne, and Ponti (2025) suggest that “a carefully designed AI tutoring system, using the best current GAI technology and deployed appropriately… can address significant known pedagogical challenges in an accessible way that can offer world-class education to any community or learning environment with an internet connection” (Kestin et al., 2025).

2HL claim that their model is able to identify gaps in a student’s learning and then provide personalised tutoring to help them fill those gaps, while students who are advancing rapidly can continue to progress. (2HL White Paper, 2024, p.26)

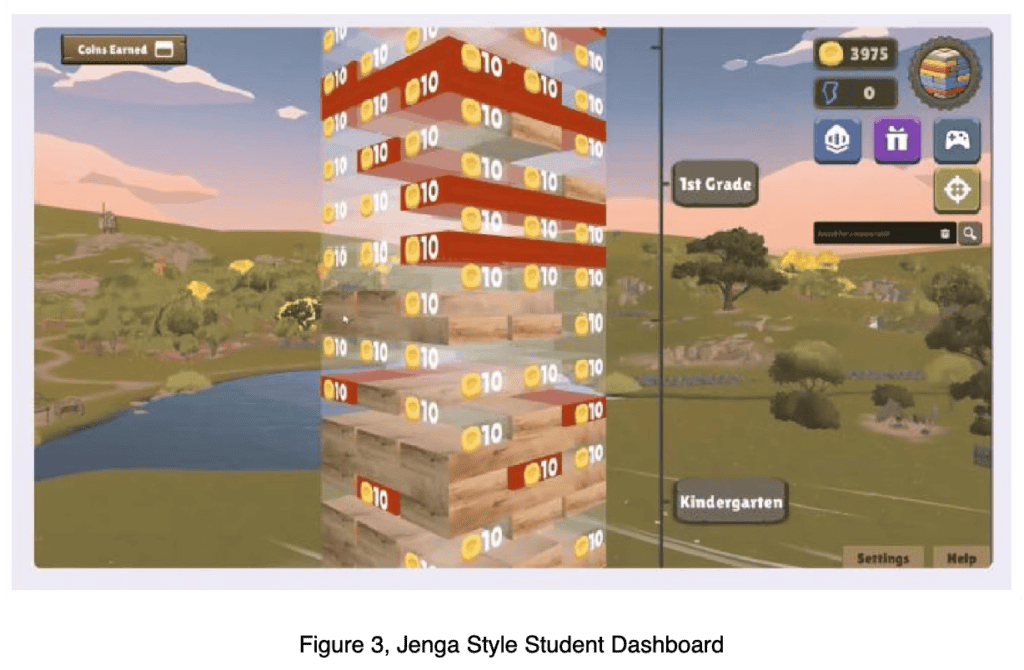

The 2HL white paper explicitly promotes the use of gamification and intensive metrics to create an education that “empowers students to crush academics” (p. 2) and promises parents “unparalleled insight into what their child knows or doesn’t know” (p. 26). A student dashboard displays a Jenga-style tower indicating how many lessons remain before a learner can progress to the next grade. Students also collect coins, shown in the top right-hand corner. Although not explicitly named in the white paper, these coins function as the school’s internal currency, known as Alpha Bucks (Feathers, 2025), which are used to extrinsically incentivise students to learn.

In one example guides offered to buy a student something from Amazon, if he retook a test to improve his score, his parents withdrew him from the Alpha School, and say the system changed him to “a work machine who would do whatever it took.” (Feathers, 2025)

As Price explained to parents, “We pay kids, literally, starting in kindergarten. Kids use their bucks to buy everything from Taylor Swift sweatshirts to squishy penguins to Legos at a school store” (as cited in Wallach, 2025). By hitting their learning metrics, they could possibly earn hundreds of dollars over the course of a school year (Feathers, 2025). The entire academic learning experience is monitored by the AI tutor and guide, with a “waste meter” displayed on the student dashboard and data shared with parents in real time. Gamified feedback and the so-called “Alpha Economy” form the fourth of five pillars of motivation at AlphaSchool (Price, 2025). This contrasts sharply with a teacher inspiring a student to learn intrinsically, simply for the sake of understanding something new; instead, motivation is increasingly tied to rewards, status, and dopamine hits from a dashboard. Silicon Valley has already developed apps, social media platforms, and video games such as Fortnite that are designed to maximise engagement and capture attention. Price’s argument for the gamification of education is that it must compete with these technology giants, whose economic models are entangled with the amount of attention they can extract from users.

The white paper states that when Alpha School first opened, they did not offer a kindergarten class because they assumed children were too young to learn via apps. “We were proven wrong – our youngest learners excelled in this environment” (2HL White Paper, 2024, p. 11). Alpha School and 2HL are therefore presented as a solution for education from kindergarten to grade 12, with even the youngest children being measured metrically and positioned in the top 1% after attending Alpha School. Metrics are used extensively throughout the paper to suggest that Alpha students are academically elite, due to the effectiveness of AI tutoring which allows them to achieve more in less time. The phrase “2x” (twice as fast) appears 21 times in the document, and percentages are repeatedly used to market high performance, such as the claim that “students averaged in the top 1–2% for every subject” (p. 4).

The white paper, however, is noticeably vague about how the remaining four hours of the school day are used once students have completed their two hours of AI-personalised learning, perhaps leaving this to the discretion of individual schools. It states that this time is intended for students to “develop life skills and explore interests.” This is referred to as “Holistic Development”, during which students work on “leadership, teamwork, public speaking, financial literacy, entrepreneurship, and socialisation through engaging workshops” (p.7). Students are described as engaging in active, hands-on activities to develop these critical life skills. Alpha’s high school programme, AlphaX, is presented as the “signature” offer, freeing afternoons to focus on an AlphaX Masterpiece that reflects your deepest passions. Formerly, between 2017 and 2020, Alpha School did not use AI; students had teachers in the morning and life-skills sessions in the afternoon, and the school reports that “their life skills, confidence, and ability to engage with adults and their peers were exceptional.” (Chris Lock, as cited in Alexander, 2025)

The policy is designed much like a pitch deck, aiming to influence parents, policymakers, and potentially investors as the model seeks to scale. It appeals particularly to parents who are dissatisfied with their child’s current schooling, are driven by data and efficiency, and want their children to achieve top-tier results, such as scoring in the top 1%. Many Alpha School campuses are located near major tech centres in the United States, such as Austin, San Francisco, New York and Miami.

This includes a campus in Brownsville, Texas, situated close to Elon Musk’s SpaceX facility, where local students can attend a summer programming camp; there are also suggestions that SpaceX has provided transportation support for the school (Wallach, 2025). Alpha also used Brownsville as a test site, charging around $10,000 per year instead of $40,000, in order to demonstrate that students from relatively lower-income families could still “learn 2x” under the model, although Joe Liemandt is reported to have said to parents that the school was opened ‘to cater to the influx of SpaceX employees to an impoverished area. (Feathers, 2025) In the first half of 2024, Alpha sent a group of students to Poland to help launch a 2HL pilot among Ukrainian refugees—an opportunity only available to those who were top academically and who had learned basic Ukrainian. (Alpha School, 2024)

In January 2025, a tuition-free charter school using 2HL opened in Arizona, extending the model further into the public sector. In the same year, 2HL became the formal parent company for all Alpha Schools, consolidating the ecosystem under a single corporate structure.

I conducted a network analysis of 2HL to better understand the ideological positioning of the model (Figure 4), as well as the mechanisms through which it is gaining influence and visibility across the United States. This analysis revealed the growing prevalence of the model, with numerous schools unaffiliated with Alpha Schools adopting 2HL technology. It also highlighted multiple instances in which 2HL, or subsidiaries linked to Trilogy Software, have made financial contributions to political organisations, suggesting an effort to engage with and potentially influence education policy. Notably, this includes multiple donations to the Texas Family Empowerment Coalition, amounting to over $1 million (Elwood, 2025). It also positions Alpha Schools on the right of American politics. Taken together, this network illustrates how closely connected these actors are and how strategically positioned they may be to scale their model and shape education policy, particularly following the signing of a presidential action on 23 April 2025 to advance the use of artificial intelligence in education (The White House, 2025).

Holistic Education Needs Subjectification

When I reflect on my own education (appendix b), although I often disliked school, I felt that I was able to develop at my own pace, without reliance on external incentives or gamification. This afforded me the space to pause, reflect, and make decisions about my own future. I first encountered Mackenzie Price and Alpha School through a podcast, and was initially impressed by the way the model was presented, particularly its reported outcomes and the promise of two hours of focused learning followed by extended periods of free time. However, after engaging more closely with the organisation’s marketing materials and first-hand accounts from students and parents, this initial impression began to shift. It became increasingly apparent that the model is, in many respects, superficial, particularly as its priorities have shifted towards measurable, seemingly at the expense of pupil wellbeing, integrated learning, and the broader purposes of education. Alpha Schools are for-profit, and its clear that they are investing heavily, with the ambition of opening charter schools across the US, and worldwide.

I believe that 2HL will be highly successful and continue to scale. This trajectory is outlined within the network analysis that I have conducted (Figure 4). The model’s decision to limit formal academic instruction to two hours a day (at least in its marketing) offers it a degree of protection against common criticisms of over-schooling or excessive screen time. Four hours each day to spend on my own interests would have appealed to me during my time at secondary school, before I encountered a broader holistic view on education, from being at Ruskin Mill. The method is likely to produce students who attain high grades, demonstrate entrepreneurial traits, and go on to achieve conventional markers of success in life — what John Ruskin described as the attainment of “a double-belled door”. Some students will thrive, while others will still be left behind, like the 8 year old, that was able to read words quickly but didn’t comprehend what he was reading, and ‘when writing by hand, he would get to the end of a line and curve down into the margins, not knowing he was supposed to move to the next line.’ (Feathers, 2025)

Practical Skills Therapeutic Education (PSTE), the pedagogical approach at Ruskin Mill, seeks to develop well-rounded individuals and provide a therapeutic form of education for learners with special educational needs. This is achieved through outdoor activities, craftwork, and a deepened connection to place. At Ruskin Mill College, there are no teachers in the traditional sense, nor are there ‘guides’ in the style of AlphaSchools. Instead, everyone acts as a guide in relation to the student—whether working as a Support Worker, Therapist, an Education, Health and Care Manager, or a tutor.

As a tutor in the garden, offering therapeutic horticulture sessions, I see my role as a facilitator who helps connect the student to the garden organism. I provide activities that support the student’s development—physically, emotionally, socially, and in cultivating confidence and self-generated, conscious action. The work is grounded in building a relationship with each student, a process that can be delicate and slow, yet profoundly meaningful. The incentive for students to engage in the garden is intrinsic; they are drawn to the sensory richness, the rhythms, and the tangible outcomes of their work. At times they may take home apple juice or something they have produced, but we do not rely on gamification or external rewards to motivate them. Instead, we trust the inherent therapeutic and educational affordances of the garden to meet them where they are.

More fundamentally, I argue that the 2HL model suffers from a lack of subjectification, one of the three domains of education identified by Biesta alongside qualification and socialisation (Biesta, 2010, pp. 73–75). As artificial intelligence continues to develop, it may become a powerful tool for academic instruction, particularly in logical or knowledge-based domains such as mathematics. In this sense, AI may enhance qualification, while the four hours of workshops may contribute to socialisation.

Biesta’s three educational functions can be broadly aligned with Steiner’s threefold social order of the economic, political, and cultural spheres (Steiner, 1919). Qualification corresponds to the economic sphere, with its emphasis on skills and efficiency; socialisation aligns with the political sphere, concerned with norms and participation; while subjectification resonates most strongly with the cultural sphere, where freedom and the emergence of the individual subject are central. From this perspective, 2HL appears disproportionately weighted towards qualification, with limited attention given to subjectification. As a result, its cultural impulse is diminished, with priorities oriented towards optimisation and performance rather than creating conditions for young people to come free and responsible subjects.

Students are contained within the algorithmic logic of the AI learning platform; however personalised it may be, it remains a system designed in advance, in which behaviour is measured and outcomes are largely predetermined. From Biesta’s perspective, subjectification cannot be automated or guaranteed (Biesta, 2010). It requires encounter, interruption, and the presence of a conscientious human teacher who addresses the student as a unique person rather than as a data point. When education is organised primarily around efficiency and optimisation, students may be given opportunities to speak or participate, yet these opportunities risk shaping them to respond in expected and standardised ways rather than allowing them to act, judge, and take responsibility as individuals.

Biesta (2010) describes this educational task as a pedagogy of interruption. Such a pedagogy does not aim to produce predictable outcomes, but instead acknowledges the fundamental limitation of education in shaping subjectivity. Paradoxically, this limitation is also education’s strength, as it is only when we abandon the idea that subjectivity can be manufactured or optimised that space opens for responsibility, ethical judgement, and personal uniqueness to emerge. While it could be argued that the initial pilot Alpha Schools made some space for subjectification, the 2HL philosophy and its scaling ambitions prioritise qualification as their primary focus, perhaps only superficially addressing other educational purposes. In this model, the student becomes a product of optimisation, but not of subjectification.

In a revealing article published in Wired magazine (Feathers, 2025), the experience of a nine-year-old student attending AlphaSchool in Brownsville, Texas, is recounted. Over time, the child began to lose weight, having started to skip lunch in an effort to remain “on track” with her learning goals. Concerned, her parents took her to a paediatrician, who provided a written note recommending that she be allowed to eat snacks throughout the school day. However, the child repeatedly returned home with the snacks still in her school bag. When questioned, she told her mother that staff at the school had informed her she had not “earned” her snacks and would only be permitted to eat once she had met her learning metrics.

Conclusion

The influx of artificial intelligence is already and will continue to transform education, as it offers a response to the current educational crisis affecting students, parents, and schools alike. Two Hour Learning and its network of schools present an elite model of education and are likely to produce strong outcomes in terms of qualification and socialisation for a small cohort of students. However, it remains unclear whether this model could generate positive outcomes for students from less affluent backgrounds, or for families unable to afford the high tuition fees that provide these schools with dynamic spaces, abundant resources, and passionate guides. More fundamentally, the model appears to marginalise subjectification, as learning is primarily organised around optimisation, measurement, and efficiency, leaving limited space for students to emerge as responsible and ethically responsive individuals in the world.

More concerning is the broader future of AI-driven education, particularly in an environment where schools compete in league tables and parents relentlessly search for the “best” school. While Two Hour Learning is effective on its own terms, it is difficult not to foresee mission creep: two hours becoming three, then four, as students, parents, and schools push for ever-better results. This represents a continuation of the banking model of education—filling students with information to be memorised through a gamified system—rather than a genuine reimagining of learning.

It is also disconcerting that technology companies such as Trilogy Software, the producer of 2HL, have so much influence over educational content and infrastructure. This shifts education away from being a free cultural space shaped by educators and towards one increasingly governed by private technological interests.

References

2HL White Paper 2024. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://heyzine.com/flip-book/2hourlearning.html\

Alexander, S. (2025). Your Review: Alpha School. Retrieved from https://www.astralcodexten.com/p/your-review-alpha-school

Alpha Anywhere. (2025). Alpha Anywhere. Retrieved December 15, 2025, from https://alphaanywhere.co/ Alpha Anywhere

Alpha School. (2025a). Locations. https://alpha.school/locations/

Alpha School. (2025b). The future of education: Joe Liemandt’s vision for Alpha School. https://alpha.school/the-future-of-education-joe-liemandts-vision-for-alpha-school/

Alpha School. (2025c). Patrick O’Shaughnessy: Joe Liemandt – Building Alpha School, and the future of education. Alpha School. https://alpha.school/joe-liemandt-and-the-future-of-education/

Alpha School. (2024, March 6). Alpha Students Travel to Poland to Help Ukrainian Refugees Learn. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gJRz612cnNg

Alpha School. (2025d, October 1). U.S. Secretary of Education visits Alpha School [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E36z4wfZpbc

Ball, S. J. (2016). Following policy: Networks, network ethnography and education policy mobilities. Journal of Education Policy, 31(5), 549–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2015.1122232

Biesta, G. (2020). Risking ourselves in education: Qualification, socialization, and subjectification revisited. Educational Theory, 70(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12411

Biesta, G. J. J. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315634319

Bloom, B. S. (1984). The 2 sigma problem: The search for methods of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring. Educational Researcher, 13(6), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X013006004

Brigham, M. P. (2023). Toward an engaged and engaging “garden” paideia for general education and beyond. Journal of General Education, 70(1–2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.5325/jgeneeduc.70.1-2.0001

Elwood, K. (2025, August 26). Alpha School brings AI-driven education to Virginia. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2025/08/26/alpha-school-virginia-ai-education/

Feathers, T. (2025). Parents fell in love with Alpha School’s promise. Then they wanted out. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/ai-teacher-inside-alpha-school/

Future of Education. (2024, August 6). Here’s how I’m fixing school [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qm6M7_TAVR0

Future of Education. (2025, November 22). I’m using AI to change education, and a lot of people are mad [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yYgbissQRK4

The Guardian. (2025, October 18). Inside San Francisco’s new AI school: Is this the future of US education? https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/oct/18/san-francisco-ai-alpha-school-tech

Invest Like The Best. (2025, August 26). Alpha School’s disruptive vision for the future of education [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a06qSgfccZs

Kestin, G., Miller, K., Klales, A., Milbourne, T., & Ponti, G. (2025). AI tutoring outperforms in-class active learning: An RCT introducing a novel research-based design in an authentic educational setting. Scientific Reports, 15(1), Article 17458. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97652-6

Mandler, P. (2014). Educating the nation I: Schools. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 24, 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0080440114000012

NBC News. (2024, September 25). This Texas private school teaches students through AI [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iqCd60xo0n0

No Priors. (2025, September 25). No Priors Ep. 133 | With Alpha School principal Joe Liemandt [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ol_pDIlL71U

OECD. (2025). How’s life for children in the digital age? OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/0854b900-en

O’Hagan, J. (2025, July 30). Alpha School’s other story wasn’t in the Times. Chalkdust & Silicon. https://medium.com/chalkdust-silicon/alpha-schools-other-story-wasn-t-in-the-times-2d9701dea44e

Peter Attia MD. (2025, September 28). 366 – Transforming education with AI and an individualized, mastery-based education model [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2g2n_CkAolg

Predictive History. (2025, August 20). Secret history #1: How power works [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ajFXykT9Joo

Price, M. (2025). From “I hate school” to “Can we skip summer?”: Alpha’s motivation formula. Alpha School. https://alpha.school/blog/from-i-hate-school-to-can-we-skip-summer-alphas-motivation-formula/

Steiner, R. (1919). The renewal of the social organism: The threefold social order and educational freedom. Rudolf Steiner Archive. https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA024/English/AP1985/GA024_index.html

Ruskin, J. (1985). Lecture I: Sesame—Of King’s treasuries. In Unto this last and other writings (p. 255). Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1865)

Sky News. (2024, August 30). School introduces UK’s first “teacherless” classroom using artificial intelligence [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MHFCVbUcwIE

The White House. (2025). Advancing artificial intelligence education for American youth. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/advancing-artificial-intelligence-education-for-american-youth/

U.S. Department of Education. (2025). Secretary McMahon visits Texas on the “Returning education to the states” tour. https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/secretary-mcmahon-visits-texas-returning-education-states-tour

Wallach, E. (2025, September 19). It’s the city’s new most expensive private school — and AI is the teacher. San Francisco Standard. https://sfstandard.com/2025/09/19/alpha-school-ai-teacher-san-francisco

Appendix

Policy Network Analysis (Appendix A)

Reflections from Secondary School (Appendix B)

When thinking about what constitutes a good education for the twenty-first century, I must confess that I have experienced education in the twenty-first century myself. Through the taught block and the questions that have arisen, I am able to reflect on my time at school with a high degree of criticality. Focusing on my experiences of secondary education, I remember waiting for break and lunchtime, when I could play football, and even enjoying the twenty minutes between the school bus arriving and the first bell, which allowed time to play football before the day began.

The bell was a prominent feature of the school day, and the day was divided into five one-hour periods. Each lesson offered little opportunity for self-expression or creativity, and we only left the confines of the classroom for physical education or to transition from one building to another. With approximately 950 lessons per year, this meant that between Years 7 and 11 I spent around 4,750 hours in lessons.

Most lessons were uninspiring, and the behaviour of other students often disrupted the class, particularly when I was placed in a lower set. These groups tended to include more students with behavioural difficulties, which frequently overwhelmed teachers and restricted their authority and ability to teach effectively. In this way, the school operated as a tiered learning environment: students in top sets were able to excel, while those in lower sets experienced increasingly constrained learning conditions.

Teachers were very fond of using PowerPoint presentations, and copying text from slides into my exercise book was a typical classroom activity. The mathematics department also subscribed to a website called MyMaths, and many sessions were spent in front of a computer playing maths games while the teacher sat back. I am sure the programme has developed significantly over the past ten years, but at the time it was a far cry from anything resembling a personalised AI tutoring experience.

Each year, before the summer holidays, our school held a cross-curricular week, which brought together students from different year groups to work collaboratively on a project. One year, each group was assigned a city from around the world and tasked with creating a pitch for hosting the Olympic Games, culminating in a presentation or opening ceremony. This required research into the city’s culture, transport networks, history, economics, as well as designing logos and branding, and—most importantly—working together as a group. This week provided opportunities to engage with subjects in context and was a stimulating experience that allowed for self-expression, experimentation, and the pursuit of individual interests within a shared task.

During this week, the normal constraints of school were temporarily suspended: lessons became fluid and self-led, and teachers’ roles shifted as they became more like guides. I remember students skipping breaks to work on final designs before presenting to the whole school. This form of context-based, purposeful learning appealed to me greatly, and similar moments could occasionally be found in other subjects, such as IT, where I designed a pizza delivery website.

Looking back, the subjects I chose to pursue at A level—Media Studies, IT, Business Studies, and Economics—were influenced by my learning style. Reflecting on school, it is striking that only physical education and art consistently offered a bodily or physical dimension to learning. After experiencing Ruskin Mill, it feels clear that mainstream education could be enriched through greater engagement with crafts and outdoor-based learning.

When I compare my own school experiences to the perceived experiences of students at Alpha School, I must confess that I am genuinely compelled by aspects of their model. Alpha School would have given me approximately 3,800 hours to explore my own interests—valuable time for someone like me, who left school unsure of what to study at university or what direction to take in life. I was never exposed to horticulture during my school years, yet it has since become a significant part of my life. In many ways, my most meaningful education took place after school: travelling abroad for the first time to India and Italy, and discovering an interest in books at the same time. School alone may have left me with a narrower perspective on the world and a more limited capacity for critical thought.

Recent Posts

In old times, humanity had an instinctive relationship with the cosmos, and agriculture was conducted with deep reverence for these rhythms. The peasant farmer was deeply attuned to them.“Let...

The fourfold human being is a concept that sits at the heart of anthroposophy and biodynamics. It is of profound importance, yet it is often misunderstood. Recently, I listened to a presentation by...